Trade tensions between China and the United States (US) have been crystallizing around a subject little known to the general public, but central to the global economy: rare earths.

Beijing has imposed restrictions on the export of its rare earths, aggravating an already tense trade war. But why are these metals so precious, and why does controlling them give China such geopolitical leverage over the US?

What are rare earths, and why are they so important?

Rare earths refer to a group of 17 chemical elements, such as neodymium, dysprosium, yttrium, gadolinium, etc., which have exceptional physical properties.

Despite their misleading name, rare earths are not actually that rare on Earth. However, they are difficult to mine, as they are not very concentrated and are often associated with radioactive substances. Their extraction is therefore costly, energy-intensive, and polluting. This makes them strategic resources.

Their importance stems from their magnetic, luminescent, or catalytic properties. They have become indispensable in the manufacture of high-tech products, including smartphones, wind turbines, electric vehicles, flat screens, lasers, as well as missiles, fighter planes, and satellites. A car's electric motor or an advanced radar system simply can't function without rare-earth magnets.

"Everything you can switch on or off likely runs on rare earths," explains Thomas Kruemmer, Director of Ginger International Trade and Investment, in remarks reported by the BBC.

China, the undisputed leader in rare earths

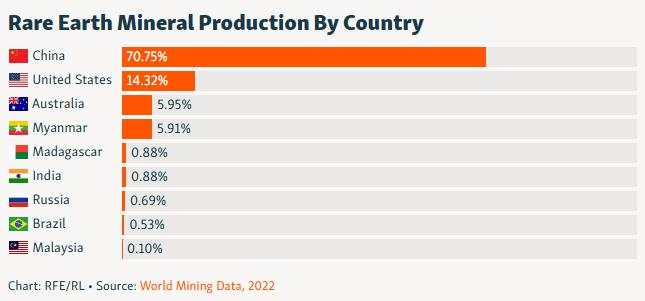

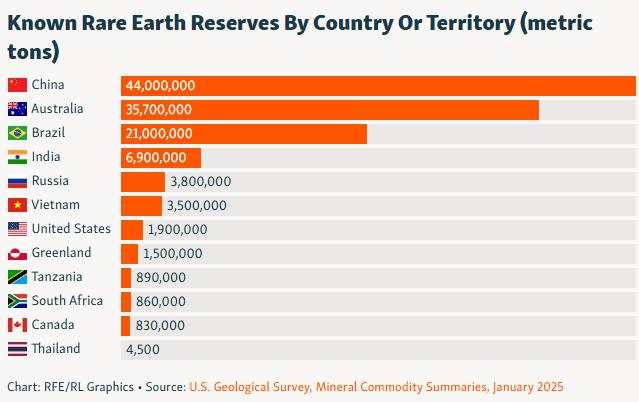

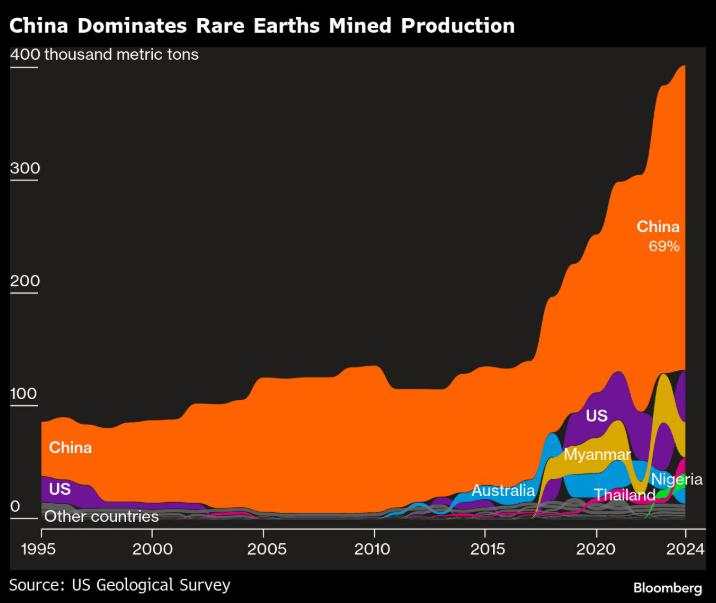

China produces around 70% of the world's rare earths, far ahead of the USA (around 14%) and Australia (around 6%).

China also holds the largest reserves of rare earths, ahead of Australia and Brazil.

This dominance is no accident: as early as the 1990s, Beijing identified these resources as strategic, investing massively in extraction, research, and industrial processing.

Western countries, including the United States, on the other hand, gradually closed their mines and relocated their production capacities to China, put off by the environmental and health costs, and attracted by China's low prices.

As a result, the majority of American technology companies are directly dependent on Chinese exports. Even rare earths mined in the US are often sent to China for processing, as China has developed unique logistics and know-how in the field of rare earth refining. In fact, according to Reuters, China refines over 90% of the total volume of rare earths extracted, a crucial step in making them industrially usable.

An economic weapon in the trade war

Faced with US economic sanctions and Washington's desire to curb China's access to cutting-edge semiconductors, Beijing has decided to strike back in a field it controls almost single-handedly: rare earths.

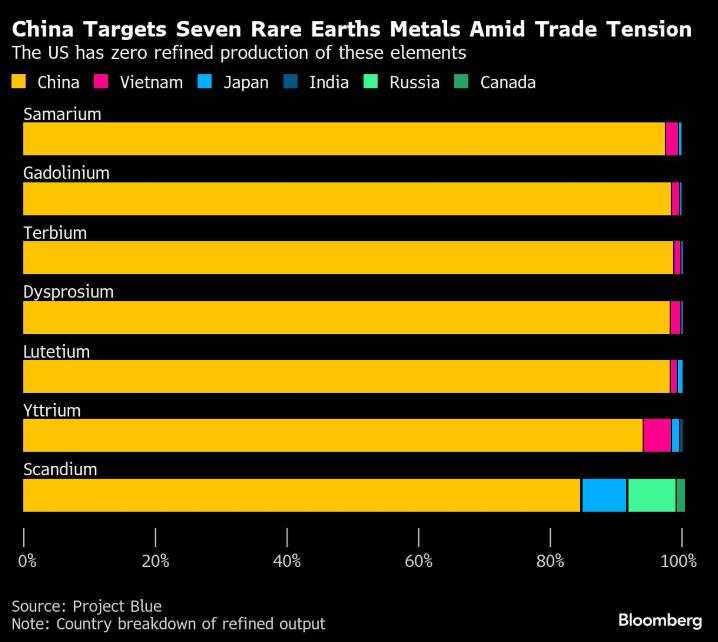

On April 4, China introduced a system of export licenses for seven strategic rare earths, affecting in particular permanent magnets used in engines, weapons, and hard disks. Without these licenses, no exporter can ship these metals abroad.

While these measures do not constitute a total embargo, they do slow down, filter, or even suspend deliveries to specific companies.

"China made that list strategically. They picked the things that are crucial for the US economy," said Mel Sanderson, a director at American Rare Earths, according to Reuters.

Faced with rising trade tensions with Washington, Beijing has begun to use rare earths as an economic weapon. Although the measure is officially "neutral" (it applies to all countries), the United States is clearly targeted. Beijing has also added several American companies to its blacklist, banned certain agricultural imports and opened antitrust investigations against American giants based in China.

Indeed, the scope of these restrictions extends far beyond American borders. Europe, equally dependent on China, is also beginning to see its supply chains threatened. Carmakers warn of imminent closures due to complex and slow licensing procedures for rare earth magnets.

Why is the USA so dependent on rare earths?

Rare earths are not just an economic issue, they are also central to national security. F-35 aircraft, nuclear submarines, and even Tomahawk missiles contain kilos of these metals. The American defense sector has no immediate alternative, and domestic reserves are limited.

But that's not all. Emerging technologies, including artificial intelligence, robotics, and renewable energies, also rely on rare-earth components. The same goes for Tesla's electric cars, Apple's iPhones, and the AI servers of the cloud giants.

America's ambition to maintain its technological supremacy depends on a stable and secure supply of these resources.

Against a backdrop of the artificial intelligence race, reindustrialization, and geopolitical tensions, this dependence has become a national security issue.

"The United States is particularly vulnerable for these supply chains. There is no heavy rare earths separation happening in the United States at present," said Gracelin Baskaran, director of the Critical Minerals Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in a report about The Consequences of China's New Rare Earths Export Restrictions.

Washington is now accusing China of "deliberately slowing down" exports despite commitments made during talks in Geneva in May, while the Pentagon warns that there is currently no heavy rare earths processing capacity on US soil.

A global race to diversify supplies

Aware of its vulnerability, the United States has started a race against time to develop a domestic industry. The only American mining site, at Mountain Pass (California), is still partially dependent on China for refining. At the same time, projects are emerging elsewhere: in Texas, Wyoming, or via the recycling of electronic waste.

But rebuilding a complete chain, from mine to magnet, will take years. That's why Washington is also looking for international alternatives, notably in Australia, Brazil, South Africa... and in even more sensitive locations.

"America must secure an end-to-end rare earth supply chain to protect its industrial and national security," said MP Materials in a statement reported by Reuters.

Ukraine, Greenland: America's quest for alternative sources

The Trump administration is actively seeking to diversify its supplies. Two territories in particular are attracting its attention: Ukraine and Greenland.

Ukraine’s subsoil is rich in lithium, uranium, and critical metals. Its rare earth reserves remain limited, but little explored. Nevertheless, as part of a strategy of diversification and economic influence, Washington reached an agreement with the Ukrainian government. In exchange for military debt relief, the United States will have privileged access to the joint exploitation of Ukraine's subsoil resources.

However, implementation of this agreement is suspended until the end of the conflict with Russia, as certain strategic sites are located in occupied zones. For its part, China is absent from the country, which reinforces American interest.

As for Greenland, an autonomous territory of Denmark rich in rare earths, it is the object of growing interest from Washington. Statements by President Donald Trump, even raising the possibility of the use of force, have illustrated the strategic importance the US attaches to it, particularly in the context of the militarization of AI.

"The use of military force will not be necessary," said US Vice President J.D. Vance, speaking from a base installed in Greenland since 1942.

Ukraine and Greenland have thus recently become points of strategic interest for the United States, not only for military or diplomatic reasons, but also for their mineral resources.

Is an agreement between China and the USA on rare earths possible?

Despite open confrontation, Beijing and Washington continue to talk. In May, a temporary agreement was signed in Geneva. China pledged to ease certain non-tariff restrictions, while the USA suspended part of its tariffs. However, the agreement remains fragile.

On the Chinese side, the authorities insist on compliance with their licensing system, presented as a "strategic control" measure justified by national security and the fight against smuggling. Licenses have been granted to certain American and European groups, but at a pace deemed "far too slow" by Washington.

Trade talks continue in June, notably in London. But tensions surrounding AI technologies, semiconductors, and military exports are likely to weigh on the negotiations.

The presence, on the American side, of Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, architect of the restrictions on technological exports, shows that rare earths are now at the heart of the global tug-of-war over industrial sovereignty.

An agreement is possible... but limited

A lasting return to free trade in rare earths seems unlikely in the short term. China does not want to give up such a powerful lever. And the United States considers these metals to be as essential to its national security as oil was in the last century.

Discussions could, however, lead to a more transparent mechanism for license applications, or to "green channels" of approval for certain civilian industries (automotive, electronics). But China is unlikely to relent on military applications.

While a logistical truce is conceivable, a strategic agreement is much less so.

A battle for industrial sovereignty

This conflict over rare earths is not simply a commercial quarrel. It reflects a more profound change: the transition from a world based on free trade to a geo-economy in which critical raw materials become levers of power. In this war for influence, China holds a decisive trump card.

The United States, for its part, is speeding up the development of a national supply chain. But this will take years. In the meantime, dependence on Chinese exports will continue to weigh heavily on Western industries.

At a time when technological tensions are intensifying and artificial intelligence is becoming a military issue, rare earths are becoming the 21st century's equivalent of Oil. The Sino-American trade war is just the beginning.

"The weaponizing of this control over critical minerals – and the race by other countries to secure alternative supplies – will be a central feature of a fractured global economy", wrote Neil Shearing, Group Chief Economist at Capital Economics.

Được in lại từ FXStreet, bản quyền được giữ lại bởi tác giả gốc.

Tuyên bố miễn trừ trách nhiệm: Quan điểm được trình bày hoàn toàn là của tác giả và không đại diện cho quan điểm chính thức của Followme. Followme không chịu trách nhiệm về tính chính xác, đầy đủ hoặc độ tin cậy của thông tin được cung cấp và không chịu trách nhiệm cho bất kỳ hành động nào được thực hiện dựa trên nội dung, trừ khi được nêu rõ bằng văn bản.

Để lại tin nhắn của bạn ngay bây giờ