Summary

Globalization has been in retreat for the past decade or so, and recent events suggest that deglobalization has further to run.

Deglobalization has had its roots in the geopolitical and economic competition between the United States and China. Recent events raise the possibility of further cleaving of the global economic order. Specifically, the possibility that the European Union goes in its own geopolitical and economic direction is no longer unfathomable.

We split the global order into hypothetical trading blocs to help us think about the potential economic implications of deglobalization. Using the Oxford Global Economic Model, we find that the effects on global GDP are essentially trivial if just the United States and China levy 15% tariffs on each other.

If the 35 countries in our US bloc slap 15% tariffs on the 32 countries in our Chinese bloc and vice versa, then the negative effects on the global economy are more significant. The model projects that the level of global real GDP under this "bipolar world" scenario would be 0.6% lower in 2029 relative to the baseline forecast that assumes no additional tariffs.

The hit to the global economy relative to baseline are more consequential in our "tripolar world" scenario in which the EU bloc levies its own 15% duties on the other two blocs, and they respond in kind. The level of global real GDP is 1.7% lower relative to baseline at the end of the decade. In nominal terms, global GDP is nearly $4 trillion lower than baseline in 2029.

If global "welfare" is measured by the level of global real GDP, then deglobalization, which we model as a world that has cleaved into trading blocs with tariffs imposed on the other blocs, is welfare reducing relative to a global economy that does not fracture.

Globalization on the wane

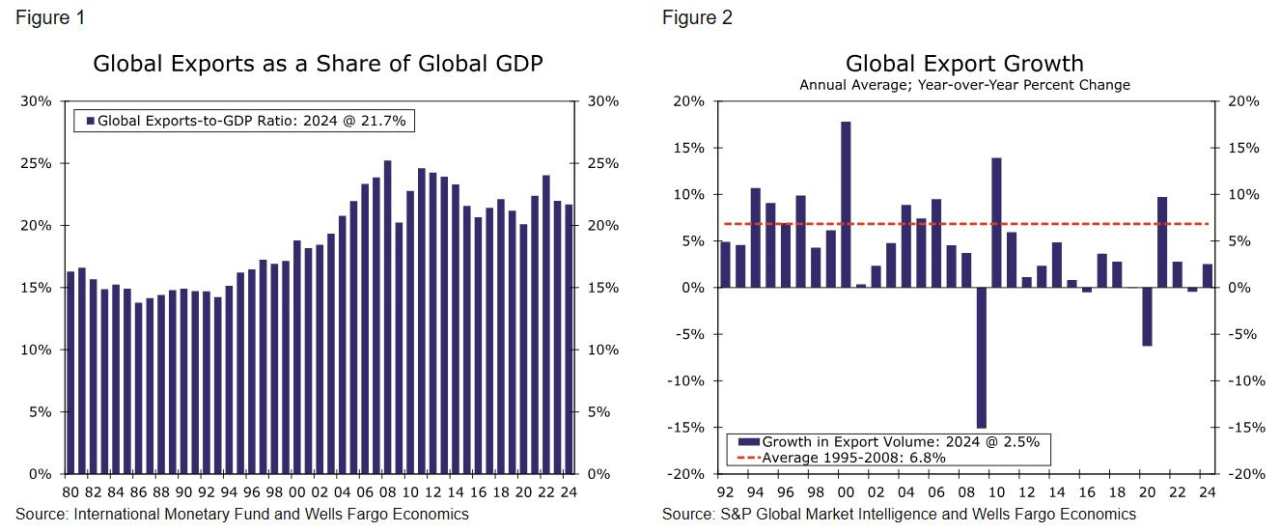

Many observers consider the 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century to be the heyday of the most recent era of globalization.1 The ratio of global exports to global GDP, which had been trendless around 15% between 1980 and the mid-1990s, rose steadily to 25% by 2008 (Figure 1). In real (i.e. volume) terms, global exports grew at an average rate of nearly 7% per annum between 1995 and 2008, nearly twice as fast as the 3.9% per annum real GDP growth rate that the global economy averaged during that period (Figure 2). Robust growth in export volumes was due, at least in part, to the strength in the global economy in the 90s and the early years of the 21st century.

Additionally, the collapse of the Soviet bloc, which opened up trade between Western and Eastern Europe, helped to boost global export growth during globalization's heyday. Trade liberalization—the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect in 1994 and China became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in late 2001—led to an intensification of trade flows as well. The atomization of production processes for many goods was another factor that boosted export growth during this period. That is, supply chains became more complex and extensive as intermediate goods were exported and re-exported on their way to assemblage into finished products.

Download The Full Special Commentary

Được in lại từ FXStreet, bản quyền được giữ lại bởi tác giả gốc.

Tuyên bố miễn trừ trách nhiệm: Nội dung trên chỉ đại diện cho quan điểm của tác giả hoặc khách mời. Nó không đại diện cho quan điểm hoặc lập trường của FOLLOWME và không có nghĩa là FOLLOWME đồng ý với tuyên bố hoặc mô tả của họ, cũng không cấu thành bất kỳ lời khuyên đầu tư nào. Đối với tất cả các hành động do khách truy cập thực hiện dựa trên thông tin do cộng đồng FOLLOWME cung cấp, cộng đồng không chịu bất kỳ hình thức trách nhiệm nào trừ khi có cam kết rõ ràng bằng văn bản.

Website Cộng đồng Giao Dịch FOLLOWME: www.followme.asia

Tải thất bại ()